The 2024 Indian general election is a massive democratic exercise unmatched in scale globally and historically. Spanning more than six weeks, with an electorate of more than 970 million registered voters, elections in the country dubbed “the world’s largest democracy” are a logistical challenge involving colossal figures.

With nearly 970 million people eligible to vote in the 2024 elections, India has once again broken its own record. The 2019 elections had 900 million registered voters, with a turnout of 67% – which means 615 million people cast their ballots in a single election.

With a population of nearly 1.4 billion people living in a country spanning more than 3 million square kilometres – around six times the size of France – holding nationwide elections on a single day is not possible due to staffing and security reasons.

Voting is therefore staggered across India’s 28 states and eight union territories over six weeks. The election is broken into seven phases based on geography and population. So while some smaller states go to the polls on a single day, larger states such as Uttar Pradesh and Maharashtra vote in different phases.

Here are some of the key dates:

April 19: Voting begins

April 26: Phase Two

May 7: Phase Three

May 13: Phase Four

May 20: Phase Five

May 25: Phase Six

June 1: Phase Seven

June 4: Votes counted nationwide, results announced

India has a first-past-the-post electoral system. Each voter chooses a candidate from those put forward, and the one with the most votes is declared elected.

Nearly 18 million youth are registered to vote for the very first time. India’s youth is an important demographic for campaigners since 40% of the country’s population is under 25, according to UN projections.

The Indian Election Commission has repeatedly promised to “enable everyone to vote” with the installation of 5.5 million electronic voting machines in more than a million polling stations across the country. They can be found in both congested cities and isolated areas in remote territories, from the snow-peaked Himalayas to the western desert of Rajasthan and tiny islands in the Indian Ocean.

Indian electoral rules mandate that a polling station must be available within 2 kilometres of every home.

This means election officials and volunteers must transport ballot papers to remote regions by any means necessary, including camels, mules, yaks or elephants, depending on the region.

In the 2019 elections for instance, election officials travelled almost 500km through winding mountain tracks to set up a polling station for a single voter in the northeastern state of Arunachal Pradesh, on the border with China.

Election officials also set up a polling booth at an altitude of 4,650m in a village in Himachal Pradesh, in the heart of the Himalayas, making it the highest polling station in the world.

A total of 15 million election workers and security personnel will be mobilised for the vote, some of them from various sectors of the civil service temporarily assigned to the polling stations.

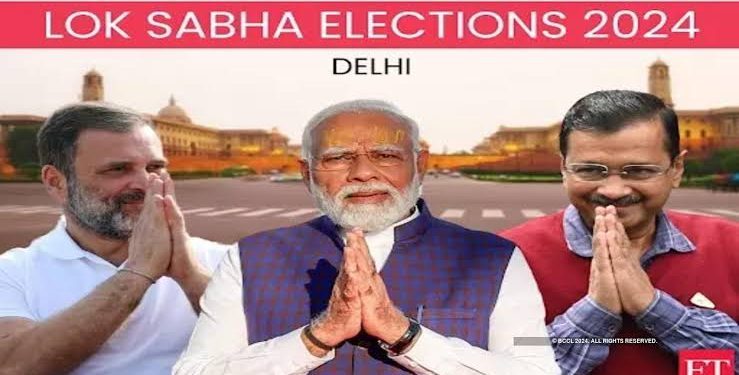

Voters will elect 543 MPs to the Lok Sabha, the lower house of parliament, for a five-year term. In addition, there are two seats reserved for the Anglo-Indian community, whose members are appointed by the India’s president.

To form a government, a political party needs 272 seats in the Lok Sabha, or 50% of the 543 elected seats.