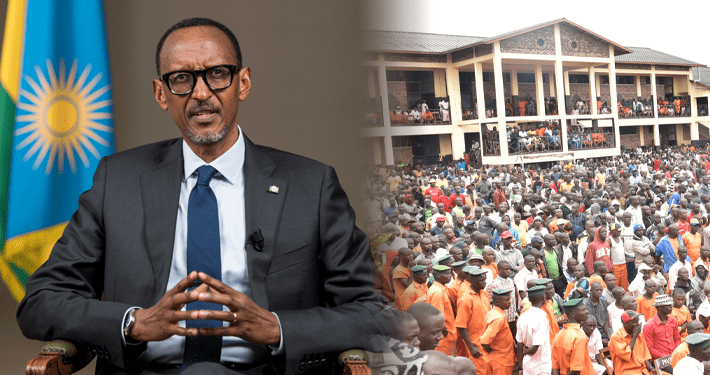

For decades, Rwandan authorities have subjected detainees, in both official and unofficial detention facilities, to ill-treatment and torture, with no accountability, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today.

Nevertheless, a landmark trial of six prison officials and 12 detainees for murder, torture, and assault at Rubavu prison, which concluded in April 2024, demonstrated that it is possible to begin to break through the entrenched practice of torture in Rwanda.

The 22-page report, ‘They Threw Me in the Water and Beat Me’: The Need for Accountability for Torture in Rwanda‘, documents torture and ill-treatment by prison officials and detainees in Nyarugenge prison in the capital, Kigali; in Rubavu prison, western Rwanda; and an unofficial detention facility in Kigali known as “Kwa Gacinya.”

Human Rights Watch found that judges ignored complaints from current and former detainees about unlawful detention and ill-treatment, creating an environment of near-total impunity.

“Our research demonstrates that prison officials have been allowed to torture detainees with impunity for years, highlighting the failures of Rwanda’s institutions mandated to safeguard detainees’ rights,” said Clémentine de Montjoye, senior Africa researcher at Human Rights Watch.

He added, “The landmark trial of prison officials provides an important first step toward accountability, but a more comprehensive response is necessary to address the deeply entrenched practice of torture in Rwanda.”

Between 2019 and 2024, Human Rights Watch interviewed more than 28 people, including 13 former detainees held in unofficial detention sites and in Rubavu and Nyarugenge prisons between 2017 and 2024.

Human Rights Watch reviewed YouTube interviews of former prisoners who described being tortured in detention and court documents relating to the trials of 53 people.

Among those were some who testified at the trial of the former director at both Nyarugenge and Rubavu prisons, Innocent Kayumba, and 17 others on charges of torture, beatings, murder, and other offences.

Former detainees told Human Rights Watch about the ordeal detainees faced in sites referred to as “Yordani” that existed in both prisons, where detainees were forced into a tank filled with dirty water, submerged, and beaten. Some said detainees were then made to run around the courtyard barefoot until they collapsed.

Mr Kayumba was director of Rubavu prison until 2019, when he was transferred to Nyarugenge, the same year as the killing of a detainee for which he would eventually stand trial.

In Nyarugenge, he put in place the same system to inflict torture, former detainees said. Human Rights Watch obtained the names of 11 prisoners whom former detainees said died in detention following beatings. Several of those cases were brought forward during Kayumba’s trial.

Human Rights Watch found a pattern of ill-treatment, mock executions, beatings, and torture at Kwa Gacinya which dates back to at least 2011.

In Kwa Gacinya, former detainees said they were held in “coffin-like” cells and were regularly beaten and forced to confess to the crimes with which they were charged, before being transferred to an official detention facility.

Human Rights Watch received information that Kwa Gacinya is now being used as a police office, although two sources connected to the security services said that the abuse continues in its basement.

On April 5, the Rubavu High Court convicted Mr Kayumba of the assault and murder of a detainee at Rubavu prison in 2019 and sentenced him to 15 years in prison and a fine of 5 million Rwandan Francs (about $3,700).

Two other Rwanda Correctional Service officers and seven prisoners, who were accused of acting under instruction, were convicted of beating and killing prisoners. Three other correctional service officials were acquitted.

The trial delivered only partial justice, Human Rights Watch said. Officials were convicted of assault and murder but acquitted of torture, which carries a heavier penalty.

Several senior prison officials were acquitted despite the damning evidence presented against them by former detainees. The prisoners who were ordered to beat fellow detainees were given longer sentences of up to 25 years.

Rwanda’s National Commission for Human Rights (NCHR) is not independent and has been unable or unwilling to report on cases of torture.

In May, Human Rights Watch submitted a third-party report to the Global Alliance of National Human Rights Institutions, which monitors national human rights institutions’ compliance with the Principles relating to the Status of National Institutions (The Paris Principles), ahead of its October review of the NCHR’s work.

Rwandan authorities routinely curtail the work of institutions with a mandate to monitor prison conditions and prevent torture. At the international level, the Rwandan government has obstructed the United Nations and other institutions from carrying out essential monitoring work in an independent manner.

In May, Human Rights Watch offered to meet with Rwanda’s justice minister and the chairperson of the NCHR to share preliminary findings of this research, but its senior researcher was denied entry upon arrival at Kigali International Airport, the report stated.

On September 10, Human Rights Watch sent letters to the justice minister and the NCHR sharing the findings but received no response.

The report urged Rwanda to comply with its own constitution and fulfil its obligations under international human rights law, in particular, the absolute prohibition on torture and cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment.

“Rwanda’s partners, particularly those that support Rwanda’s justice sector, such as the European Union, should press Rwanda’s government to intensify efforts to hold all those responsible for torture accountable.

“The government should conduct a comprehensive investigation into torture in Rwanda’s prisons. To lend credibility to the investigation, the government should request the assistance of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights and UN experts and publicly report on its findings.

“Finally, Rwanda should cooperate with the UN Committee against Torture and submit its state party report, due since December 2021, and permit the Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment to resume its visit to detention facilities unhindered,” stated the rights organisation.