GAO, MALI – During a grueling, weekslong mission in northern Mali, French soldiers were confronted by a familiar threat: Extremists trying to impose the same strict Islamic rule that preceded France’s military intervention here more than eight years ago.

Traumatized residents showed scars on their shoulders and backs from whippings they endured after failing to submit to the jihadis’ authority.

“We were witness to the presence of the enemy trying to impose Shariah law, banning young children from playing soccer and imposing a dress code,” said Col. Stephane Gouvernet, battalion commander for the recent French mission dubbed Equinoxe.

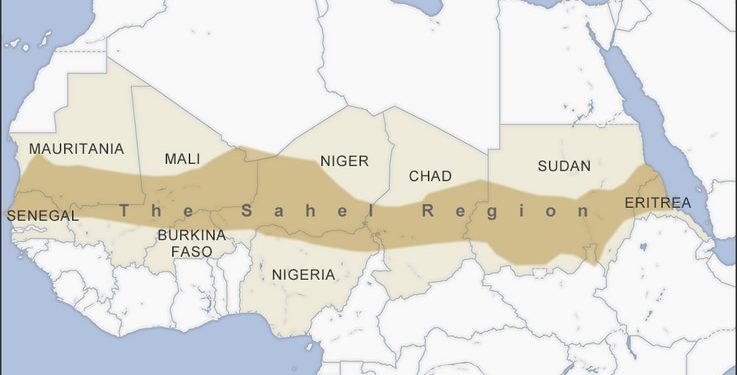

France is preparing to reduce its military presence here in West Africa’s Sahel region – the vast area south of the Sahara Desert where extremist groups are fighting for control. In June, French President Emmanuel Macron announced the end of Operation Barkhane, France’s seven-year effort fighting extremists linked to al-Qaida and the Islamic State in Africa’s Sahel region. France’s more than 5,000 troops will be reduced in the coming months, although no timeframe has been given.

Instead, France will participate in a special forces unit with other European countries and African countries will be responsible for patrolling the Sahel.

The move comes after years of criticism that France’s military operation is simply another reiteration of colonial rule. But the shift also takes place amid a worsening political and security crisis in the region. In May, Mali had its second coup in nine months.

Although officials of Mali’s government have been able to return to some towns once overrun by jihadis, for the first time since 2012, there are reports of extremists amputating hands to punish suspected thieves – a throwback to the Shariah law imposed in northern Mali prior to the French military intervention.

There have been spikes, too, in extremist attacks in Burkina Faso and Niger, sparking concern that the reduction of the French force will create a security void in the Sahel region that will be quickly filled by the jihadis.

“If an adequate plan is not finalized and in place, the tempo of attacks on local forces could rise across the region over the coming weeks, as jihadists attempt to benefit from a security vacuum,” said Liam Morrissey, chief executive officer for MS Risk Limited, a British security consultancy operating in the Sahel for 12 years.

While France has spent billions on its anti-jihadi campaign, called Operation Barkhane, Sahel experts say that it never dedicated the necessary resources to defeat the extremists, said Michael Shurkin, director of global programs at 14 North Strategies, a consultancy based in Dakar, Senegal.

“They have always been aware that their force in the Sahel is far too undersized to accomplish anything like a counterinsurgency campaign,” he said.

France has several thousand troops covering more than 1,000 kilometers of terrain in the volatile region where the borders of Niger, Mali and Burkina Faso meet. Alerts about attacks are often missed or responded to hours later, especially in remote villages. Operations rely heavily on the French air force, which conduct airstrikes, transport troops and deliver equipment. The desert is harsh with temperatures reaching near 50 degrees Celsius, exhausting troops and requiring additional maintenance for equipment.

The Associated Press spent the days before Macron’s announcement accompanying the French military in the field, where pilots navigated hostile terrain in the pitch dark to retrieve troops after a long operation.

Some soldiers questioned if the fight was worth it. “What are we doing here anyway?” asked one soldier after Macron’s announcement. The AP is not using his name because he was not authorized to speak to the media.

Others acknowledged the jihadis are a long-term threat. “We are facing something that is going to be for years. For the next 10 years you will have terrorists in the area,” Col. Yann Malard, airbase commander and Operation Barkhane’s representative in Niger, told the AP.

The French strategy has been to weaken the jihadis and train local forces to secure their own countries. Since arriving, it has trained some 18,000 soldiers, mostly Malians, according to a Barkhane spokesperson, but progress is slow. Most Sahelian states are still too poor and understaffed to deliver the security and services that communities desperately need, analysts and activists say.

State forces have also been accused of committing human rights abuses against civilians, deepening the mistrust, said Alex Thurston, assistant professor of political science at the University of Cincinnati.

Since 2019 there have been more than 600 unlawful killings by security forces in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger during counterterrorism operations, according to Human Rights Watch. France’s Barkhane, too, has been accused of possible violations of international humanitarian law and human rights, after an airstrike in Mali in January killed 22 people, 19 of whom were civilians, according to a report by the U.N. peacekeeping mission in Mali.

Soldiers agree that there are limits to what can be achieved militarily and without political stability in the Sahel, jihadis have the edge.

“We don’t have an example of a big win in counterinsurgency, and it’s difficult to achieve that in the current environment because for an insurgency to win they just need to stay alive,” said Vjatseslav Senin, senior national representative for the 70 Estonian troops who are fighting alongside the French in Barkhane.

Some of those living in the Sahel fear what hard-fought gains have been made will unravel all too quickly.

Ali Toure, a Malian working in the French military base in Gao warned that “if the French army leaves Mali, jihadis will enter within two weeks and destroy the country.”