When Yoweri Museveni seized power in Uganda in 1986, he said, “The problem of Africa in general and Uganda in particular is not the people but leaders who want to overstay in power.”

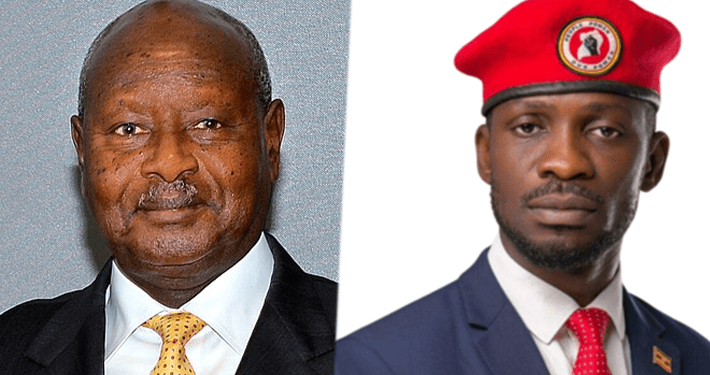

The 81-year-old president and former rebel is seeking a seventh term in office on Thursday after nearly four decades leading the East African nation, the vast majority of whose citizens have never known any other leader.

Mr Muzeveni’s main rival in Thursday’s presidential election is Bobi Wine, a 43-year-old pop star.

Political analysts say that while Mr Museveni’s victory is all but certain, the road ahead is clouded by uncertainty, with the president showing signs of frailty.

“The big question looming over the election is the question of succession,” university professor Titeca said, reflecting on the rapid rise of Muhoozi Kainerugaba, Museveni’s son and Uganda’s military chief.

Uganda’s opposition has accused Mr Museveni of fast-tracking Mr Kainerugaba’s military career to prepare him to eventually succeed him, even with the 51-year-old frequently taking to X to make inflammatory remarks, while veteran politicians who once fought alongside Mr Museveni in the bush have been sidelined.

The election outcome could determine Mr Museveni’s next move, with a poor showing potentially prompting him to promote other party members and deflect criticism of an outright dynastic succession, said former newspaper editor Charles Onyango-Obbo.

“This is less about the results that will be announced, and more about the mood on the ground,” Mr Onyango-Obbo added, saying that a handover could be some years away. “Museveni is more frail now, but he is a workaholic… he will not leave even if he needs to use a walking stick.”

Mr Museveni came to power on a wave of optimism after leading insurgencies against autocratic governments.

That goodwill was soon squandered amid allegations of graft and authoritarianism.

“Corruption has been central to his rule from the beginning,” Kristof Titeca, a professor at the University of Antwerp, told Reuters.

Mr Museveni has acknowledged that some government officials have engaged in corrupt practices, but says all those caught have been prosecuted.

The canny political strategist has also cultivated foreign allies by embracing the security priorities of Western powers, deploying peacekeepers to hotspots such as Somalia and South Sudan and welcoming huge numbers of refugees to Uganda.

In his own country, his record has been mixed.

His government won praise for tackling the AIDS epidemic and for beating back the Lord’s Resistance Army rebel group that brutalised Ugandans for nearly 20 years.

But widespread corruption hollowed out state services, and just one in four Ugandan children who enter primary school make it to secondary school, according to the United Nations Children’s Fund, while well-paid jobs remain largely out of reach for many.

There, he founded a militant movement that eventually helped force out President Idi Amin, with Milton Obote taking over as Uganda’s leader in 1980.

Mr Obote was toppled in a 1985 coup.

The following year, the military wing of Museveni’s National Resistance Movement overthrew Tito Okello, who had become president.

“This is not a mere change of guard,” Mr Museveni said at his swearing-in. “This is a fundamental change in the politics of our government.”

His efforts to attract foreign investment, establish order and raise the standard of living were initially applauded by the West.

But as Uganda’s economy picked up, so did public anger over corruption.

Under a privatisation programme, dozens of state enterprises were sold to Mr Museveni’s relatives and cronies at fire-sale prices, according to parliamentary reports, which said some of the proceeds were embezzled.

Kizza Besigye, Mr Museveni’s doctor during his years in the bush, fell out with him, accusing him of presiding over corruption and rights abuses.

Mr Museveni has won all six presidential elections he contested, including four against Mr Besigye, who was arrested in 2024 and faces treason charges.

In 2005, parliament scrapped presidential term limits, a move critics said was aimed at letting him keep power for life.

Mr Museveni’s election opponents rejected the election results over alleged irregularities. But the authorities denied the allegations and police cracked down on demonstrations by opposition supporters.

Mr Museveni dismissed criticism from Western powers, saying in 2006, “If the international community has lost confidence in us, then that is a compliment because they are habitually wrong.”

He also sought to cultivate ties with other countries, including China, Russia, Iran and the United Arab Emirates, to reduce Uganda’s dependence on the West.

The discovery of substantial oil deposits buoyed his status, leading to agreements with energy giants TotalEnergies and CNOOC to build an export pipeline.

(Reuters/NAN)